by Ran Britt

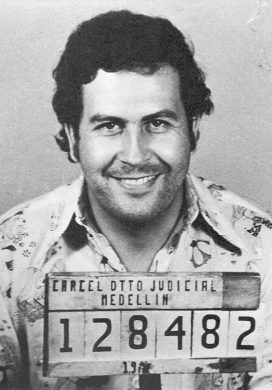

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born to farmer Abel de Jesus Dari Escobar and elementary school teacher Hermilda Gaviria on December 1, 1949, on a small farm in Rionegro, Colombia. He was the third of Abel and Hermilda's seven children. Two years later, Pablo and his older brother Roberto were sent to live with their grandmother, who lived 25 miles away in Envigado, a suburb of Colombia's second-largest city, Medellin. Escobar majored in political science at the Universidad de Antioquia before dropping out due to his inability to pay tuition.

His first foray into crime was stealing gravestones. He'd sell them to the families of the recently deceased after sanding them down. Escobar's grandfather was reportedly a Colombian bootlegger, illegally transporting tapetusa in empty caskets and hollowed-out eggs.

He also spent time as a car thief and small-time marijuana dealer before working as a bodyguard for Colombian drug traffickers during his early 20s. For a time, Escobar worked for electronics smuggler Alvaro Prieto. During that same period, he kidnapped a Medellin businessman before setting him free in exchange for a $100,000 ransom. He eventually went into business for himself smuggling cigarettes.

In 1974, Escobar was arrested for car theft. In 1975, he reportedly murdered Medellin cocaine trafficker Fabio Restrepo, from whom he’d bought 14 kilograms of powder, and assumed his narcotics operation.

That same year, Escobar started buying Bolivian coca paste, which he and his brother, Roberto, would process inside a two-story home in Medellin. They would then transport the cocaine, hidden in aircraft tires, to Panama by plane once a week. Offering bribes to airport managers, upwards of $300,000 round trip, assured that the narcotics were allowed into the country.

In 1974, Escobar was arrested for car theft. In 1975, he reportedly murdered Medellin cocaine trafficker Fabio Restrepo, from whom he’d bought 14 kilograms of powder, and assumed his narcotics operation.

That same year, Escobar started buying Bolivian coca paste, which he and his brother, Roberto, would process inside a two-story home in Medellin. They would then transport the cocaine, hidden in aircraft tires, to Panama by plane once a week. Offering bribes to airport managers, upwards of $300,000 round trip, assured that the narcotics were allowed into the country.

In May of 1976, Escobar and a number of his associates were arrested for possession in Medellin upon returning from Ecuador with 18 kilograms of cocaine. Following an unsuccessful attempt to bribe a Medellin judge, he allegedly ordered the murders of the two officers who made the arrest and the charges were subsequently dropped. As a result, he was released from jail a mere three months after his arrest. During this time Escobar’s organization was known as “Los Pablos”.

The 5'6" Escobar reportedly made a habit of offering those he found uncooperative: "Plata o plomo?", which translates to "Silver or lead?" -- meaning, he offered the choice of money (silver) or bullets (lead).

He eventually partnered with brothers Jorge Luis, Juan David and Fabio Ochoa, who ran their own cocaine business, creating the organization that would come to be known as the Medellin Cartel.

Roberto headed a team of 10 accountants for the organization, while Pablo was effectively the CEO.

In March of 1976, Escobar married Maria Victoria Henao, with whom he fathered his children, Juan Pablo and Manuela.

Within two years, the cartel was exporting 35 kilograms of cocaine per month. The organization imported Bolivian and Peruvian coca leaves, processed them into cocaine in Colombia and Venezuela, and finally exported the product to the U.S. by way of the Caribbean and Central America.

The 5'6" Escobar reportedly made a habit of offering those he found uncooperative: "Plata o plomo?", which translates to "Silver or lead?" -- meaning, he offered the choice of money (silver) or bullets (lead).

He eventually partnered with brothers Jorge Luis, Juan David and Fabio Ochoa, who ran their own cocaine business, creating the organization that would come to be known as the Medellin Cartel.

Roberto headed a team of 10 accountants for the organization, while Pablo was effectively the CEO.

In March of 1976, Escobar married Maria Victoria Henao, with whom he fathered his children, Juan Pablo and Manuela.

Within two years, the cartel was exporting 35 kilograms of cocaine per month. The organization imported Bolivian and Peruvian coca leaves, processed them into cocaine in Colombia and Venezuela, and finally exported the product to the U.S. by way of the Caribbean and Central America.

The cocaine would routinely be airdropped over the Atlantic Ocean and retrieved by speedboat. Sometimes pilots would simply drop it over the Florida mainland.

Some of the cocaine made its way into destination countries hidden in other prodcts. Chemists employed by the cartel developed methods of liquefying cocaine and mixing it with items as diverse as plastic and Chilean wine. Some products such as flowers, jeans and Colombian lumber were soaked with the substance. The cocaine would be separated by the intended recipients.

The cartel built enormous self-sustaining labs in the Colombian jungle for processing the cocaine. One such lab, near the border of Venezuela, had its own airstrip, employed 200 workers and turned out 10,000 kilograms every two weeks.

Some of the cocaine made its way into destination countries hidden in other prodcts. Chemists employed by the cartel developed methods of liquefying cocaine and mixing it with items as diverse as plastic and Chilean wine. Some products such as flowers, jeans and Colombian lumber were soaked with the substance. The cocaine would be separated by the intended recipients.

The cartel built enormous self-sustaining labs in the Colombian jungle for processing the cocaine. One such lab, near the border of Venezuela, had its own airstrip, employed 200 workers and turned out 10,000 kilograms every two weeks.

Escobar purchased a mansion in Miami Beach in 1980 and the following year he bought an $8.3 million apartment complex in Florida.

Escobar financed the construction of 1,000 homes for Medellin residents - who were only responsible for paying the utilities. The neighborhood became known as "Barrio Pablo Escobar".

Escobar moved to Puerto Triunfo and settled into a 7,000-acre, $60 million estate, which he named Hacienda Napoles. The property boasted 24 lakes, a garden containing 100,000 fruit trees and a private zoo. Atop the front gate sat a plane, which Escobar said was used to ferry his first shipment of cocaine.

In 1982, Escobar was elected to Colombia's Congress as an alternate Liberal Party MP. He resigned in 1984 when Justice Minister Rodgrigo Lara Bonilla made his drug trafficking activities public knowledge.

Escobar allegedly ordered the April 30, 1984 killing of Bonilla. Escobar's chief sicario (assassin), David Ricardo Prisco Lopera, was suspected of carrying out the order, armed with a MAC-10 machine pistol. Following Bonilla's death, both Escobar and fellow Medellin cartel decision-makers Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha and Jorge Ochoa fled to Panama until the heat died down. That May, Escobar and Ochoa attempted to negotiate with then Colombian President Belisario Betancur for amnesty via former Colombian President Alfonso Lopes.

Escobar financed the construction of 1,000 homes for Medellin residents - who were only responsible for paying the utilities. The neighborhood became known as "Barrio Pablo Escobar".

Escobar moved to Puerto Triunfo and settled into a 7,000-acre, $60 million estate, which he named Hacienda Napoles. The property boasted 24 lakes, a garden containing 100,000 fruit trees and a private zoo. Atop the front gate sat a plane, which Escobar said was used to ferry his first shipment of cocaine.

In 1982, Escobar was elected to Colombia's Congress as an alternate Liberal Party MP. He resigned in 1984 when Justice Minister Rodgrigo Lara Bonilla made his drug trafficking activities public knowledge.

Escobar allegedly ordered the April 30, 1984 killing of Bonilla. Escobar's chief sicario (assassin), David Ricardo Prisco Lopera, was suspected of carrying out the order, armed with a MAC-10 machine pistol. Following Bonilla's death, both Escobar and fellow Medellin cartel decision-makers Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha and Jorge Ochoa fled to Panama until the heat died down. That May, Escobar and Ochoa attempted to negotiate with then Colombian President Belisario Betancur for amnesty via former Colombian President Alfonso Lopes.

By 1985, the Medellin Cartel was making $60 million per day. The organization spent $2,500 per month on rubber bands used to hold stacks of cash together.

Escobar's personal fortune grew so vast that he was forced to store much of the cash in warehouses, the walls of homes belonging to the homes of cartel members and Colombian fields. Some of the money would routinely be eaten by rats. The cash would have to be moved periodically in order to prevent it from molding. Each year, he'd expect a 10% loss, which amounted to billions annually, due to these issues.

In July of 1985, he allegedly ordered the murder of Superior Court Judge Tulio Castro Gil.

In November, Pro-Cuba leftist guerilla group M-19 stormed Colombia's Supreme Court headquarters in Bogota and killed 11 justices. The raid is widely believed to have been sponsored by the Medellin cartel.

In 1986, Escobar and four other high-ranking members of the Medellin cartel were indicted by a federal grand jury in Miami. They were all accused of smuggling more than 58 tons of cocaine into the U.S. between 1978-1986.

In November of 1986, Escobar allegedly ordered the killing of former anti-narcotics police Colonel Jaime Ramirez.

On the night of December 17, Guillermo Cano, editor-in-chief of Colombia's second-largest newspaper, El Espectador, was shot to death while driving away from the paper's offices by two assailants on a motorcycle. It was widely speculated that Escobar, who had been the subject of critical articles published by the paper, had ordered Cano's killing. In the days following the murder, local police killed a woman and four men they believed to be connected after a 90-minute shootout with the suspects in a luxury apartment.

Escobar's personal fortune grew so vast that he was forced to store much of the cash in warehouses, the walls of homes belonging to the homes of cartel members and Colombian fields. Some of the money would routinely be eaten by rats. The cash would have to be moved periodically in order to prevent it from molding. Each year, he'd expect a 10% loss, which amounted to billions annually, due to these issues.

In July of 1985, he allegedly ordered the murder of Superior Court Judge Tulio Castro Gil.

In November, Pro-Cuba leftist guerilla group M-19 stormed Colombia's Supreme Court headquarters in Bogota and killed 11 justices. The raid is widely believed to have been sponsored by the Medellin cartel.

In 1986, Escobar and four other high-ranking members of the Medellin cartel were indicted by a federal grand jury in Miami. They were all accused of smuggling more than 58 tons of cocaine into the U.S. between 1978-1986.

In November of 1986, Escobar allegedly ordered the killing of former anti-narcotics police Colonel Jaime Ramirez.

On the night of December 17, Guillermo Cano, editor-in-chief of Colombia's second-largest newspaper, El Espectador, was shot to death while driving away from the paper's offices by two assailants on a motorcycle. It was widely speculated that Escobar, who had been the subject of critical articles published by the paper, had ordered Cano's killing. In the days following the murder, local police killed a woman and four men they believed to be connected after a 90-minute shootout with the suspects in a luxury apartment.

Following a three-year DEA investigation, nicknamed Operation Pisces, Escobar, Fabio Ochoa-Restrepo and 113 others were indicted on drug-trafficking charges on May 6, 1987. Operation Pisces also culminated in the seizure of 19,000 pounds of the Medellin cartel's cocaine and cash and assets estimated at $49 million. The investigation also led to 54 bank accounts in Panama tied to the cartel being frozen. Over the span of the op, undercover DEA agents laundered $116 million of the cartel's money. In July, convicted Cuban-American racketeer Ramon Milian-Rodriguez testified before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee on terrorism and narcotics that the Medellin cartel owned majority interests in seven Panamanian banks. He further testified that in 1979 he'd negotiated for Panama's de facto leader, General Manuel Antonio Noriega, head of the Panama Defense Forces since 1983, to receive a 1.5% cut of the narcotics traffic and related fund transfers, upwards of $200 million per month, that moved through the country in exchange for allowing the cartel to conduct business there. According to Milian-Rodriguez, who was sentenced to a 35-year prison term in 1985, Noriega also allowed the Colombians to set up cocaine-processing plants in Panama.

In January of 1988, Escobar allegedly ordered the death of Attorney General Carlos Mauro Hoyos.

In 1989, Forbes magazine placed Escobar at #7 on their list of the world's richest men, citing his estimated net worth at $3 billion.

On August 18, 1989, presidential candidate Senator Luis Carlos Galan, running on a platform promise to extradite drug traffickers if elected, was shot to death by an Uzi-wielding gunman while giving a campaign speech. Four judges were also killed by a cartel hit squad, led by Alfredo Vaquero, who was charged for the murders on August 20. The government responded to the murders by declaring that suspects charged with drug trafficking would be extradited to the U.S. and their property seized.

Colombia's Administrative Security Department, headed by General Miguel A. Maza Marquez, discovered that Escobar and Gacha had commissioned the formation of paramilitary units trained in assassination techniques by four Israeli commandos, including Colonel Yair Klein. During a raid on the home of alleged sicario (assassin)-recruiter Henry Perez, the DAS (Colombian police's primary intelligence agency) recovered a 48-minute long videotape of Klein training 50 recruits. The training included recruits detonating bombs and simulating drive-by shootings, assaults on towns and ambushes using Israeli Uzi sub-machine guns, Soviet AK-47 assault rifles and American AR-15 assault rifles. Aside from assassinations, the squads were also tasked with protecting the cartel's crops and labs.

In late August, the Bush Administration announced that it would send $65 million in military equipment, including 20 helicopters, to aid in the continued effort to dismantle the cartel's operations. By the time of the announcement, at least 100 planes tied to the cartel had already been seized.

In September and October, Escobar and Gacha reportedly ordered over 150 dynamite attacks that led to the deaths of 10 people. On October 16, four employees of Vanguardia Liberal newspaper were killed in Bucaramanga when over 100 pounds of dynamite in a parked car was detonated. The paper was especially critical of both Escobar and Gacha and supported the Colombian government's efforts to apprehend them. The government, in fact, distributed wanted posters for each, offering a $250,000 reward for information leading to their capture.

Due to the subsequent government crackdown, marked by widespread property seizures, the Medellin cartel reduced its imports, resulting in increased cocaine prices in the U.S.

That November, flight 203, of the Colombian airline Avianca, crashed following the detonation of an on-board bomb, killing 111 people. The flight, which took off from El Dorado International Airport in Bogota was headed for Cali, Colombia, located 190 miles southwest. One of Escobar's enforcers, Dandeny Munoz Mosquera, would later be charged with placing the bomb on the plane at the former's behest.

Following the December 15 death of Gacha during a shootout with police. Escobar became the most-wanted man in Colombia.

On December 20, men who'd been hired by Escobar kidnapped Alvaro Diego Montoya as he was leaving his Bogota office. Montoya, the president of a financial services company, happened to the the son of German Montoya, Colombian president Virgilio Barca's secretary general.

Also in December, the DAS (Department of Administrative Security) headquarters was bombed -- an attack that killed 50 and injured 200.

That same year, Escobar was accused of ordering the murder of the head of Colombia's National Police Anti-Narcotics Unit, Jaime Gomez Ramirez.

In 1990, police initiated "Operation Apocalypse", a manhunt aimed at capturing Escobar. Meanwhile, Escobar reportedly offered a $4,000 bounty for every police officer killed.

On March 22, Colombian presidential candidate Bernardo Jaramillo was killed, allegedly by Escobar's order. That same month, Cesar Gaviria Trujillo was elected president. On April 3, police tracked Escobar to a residence in La Miel. However, he'd vacated the premises one day earlier. On April 26, another presidential candidate, Carlos Pizzaro, was killed.

In early May, the Colombian army dealt Escobar a blow when they conducted a series of jungle raids that culminated in a seizure of 18 tons of cocaine. Around the same time, two Colombians tied to Escobar were arrested in Florida for reportedly attempting to buy 120 surface-to-air Stinger missiles.

In the spring of 1990, Escobar was rumored to have adopted the habit of smoking basuco, coca paste mixed with marijuana, and began traveling with six bodyguards led by his chief of security, John "Pinina" Jairo Arias Tascon. No longer displaying his wealth, for fear of attracting too much attention, Escobar often moved throughout the country riding in the trunk of taxis.

In August of 1990, Escobar's cousin, Gustavo de Jesus Gaviria, was shot to death during a police raid. On August 30, six reporters were kidnapped at Escobar's behest. Two more were kidnapped on September 19, though four of the eight were released one-at-a-time in November and December. In September, Colombia's President Cesar Gaviria, who had worked as Luis Carlos Galan's campaign manager and had taken office himself in August, offered leniency and a promise not to extradite any cartel members who turned themselves in to authorities, with the condition that the individual confess to every crime he committed. On November 23, the Medellin cartel proposed a truce to the Colombian government, offering to release several kidnapped hostages in exchange for an official ban on extradition to the U.S. Justice Minister Jaime Giraldo in turn conceded that cartel members who surrendered would only be required to confess to a single crime.

In January of 1988, Escobar allegedly ordered the death of Attorney General Carlos Mauro Hoyos.

In 1989, Forbes magazine placed Escobar at #7 on their list of the world's richest men, citing his estimated net worth at $3 billion.

On August 18, 1989, presidential candidate Senator Luis Carlos Galan, running on a platform promise to extradite drug traffickers if elected, was shot to death by an Uzi-wielding gunman while giving a campaign speech. Four judges were also killed by a cartel hit squad, led by Alfredo Vaquero, who was charged for the murders on August 20. The government responded to the murders by declaring that suspects charged with drug trafficking would be extradited to the U.S. and their property seized.

Colombia's Administrative Security Department, headed by General Miguel A. Maza Marquez, discovered that Escobar and Gacha had commissioned the formation of paramilitary units trained in assassination techniques by four Israeli commandos, including Colonel Yair Klein. During a raid on the home of alleged sicario (assassin)-recruiter Henry Perez, the DAS (Colombian police's primary intelligence agency) recovered a 48-minute long videotape of Klein training 50 recruits. The training included recruits detonating bombs and simulating drive-by shootings, assaults on towns and ambushes using Israeli Uzi sub-machine guns, Soviet AK-47 assault rifles and American AR-15 assault rifles. Aside from assassinations, the squads were also tasked with protecting the cartel's crops and labs.

In late August, the Bush Administration announced that it would send $65 million in military equipment, including 20 helicopters, to aid in the continued effort to dismantle the cartel's operations. By the time of the announcement, at least 100 planes tied to the cartel had already been seized.

In September and October, Escobar and Gacha reportedly ordered over 150 dynamite attacks that led to the deaths of 10 people. On October 16, four employees of Vanguardia Liberal newspaper were killed in Bucaramanga when over 100 pounds of dynamite in a parked car was detonated. The paper was especially critical of both Escobar and Gacha and supported the Colombian government's efforts to apprehend them. The government, in fact, distributed wanted posters for each, offering a $250,000 reward for information leading to their capture.

Due to the subsequent government crackdown, marked by widespread property seizures, the Medellin cartel reduced its imports, resulting in increased cocaine prices in the U.S.

That November, flight 203, of the Colombian airline Avianca, crashed following the detonation of an on-board bomb, killing 111 people. The flight, which took off from El Dorado International Airport in Bogota was headed for Cali, Colombia, located 190 miles southwest. One of Escobar's enforcers, Dandeny Munoz Mosquera, would later be charged with placing the bomb on the plane at the former's behest.

Following the December 15 death of Gacha during a shootout with police. Escobar became the most-wanted man in Colombia.

On December 20, men who'd been hired by Escobar kidnapped Alvaro Diego Montoya as he was leaving his Bogota office. Montoya, the president of a financial services company, happened to the the son of German Montoya, Colombian president Virgilio Barca's secretary general.

Also in December, the DAS (Department of Administrative Security) headquarters was bombed -- an attack that killed 50 and injured 200.

That same year, Escobar was accused of ordering the murder of the head of Colombia's National Police Anti-Narcotics Unit, Jaime Gomez Ramirez.

In 1990, police initiated "Operation Apocalypse", a manhunt aimed at capturing Escobar. Meanwhile, Escobar reportedly offered a $4,000 bounty for every police officer killed.

On March 22, Colombian presidential candidate Bernardo Jaramillo was killed, allegedly by Escobar's order. That same month, Cesar Gaviria Trujillo was elected president. On April 3, police tracked Escobar to a residence in La Miel. However, he'd vacated the premises one day earlier. On April 26, another presidential candidate, Carlos Pizzaro, was killed.

In early May, the Colombian army dealt Escobar a blow when they conducted a series of jungle raids that culminated in a seizure of 18 tons of cocaine. Around the same time, two Colombians tied to Escobar were arrested in Florida for reportedly attempting to buy 120 surface-to-air Stinger missiles.

In the spring of 1990, Escobar was rumored to have adopted the habit of smoking basuco, coca paste mixed with marijuana, and began traveling with six bodyguards led by his chief of security, John "Pinina" Jairo Arias Tascon. No longer displaying his wealth, for fear of attracting too much attention, Escobar often moved throughout the country riding in the trunk of taxis.

In August of 1990, Escobar's cousin, Gustavo de Jesus Gaviria, was shot to death during a police raid. On August 30, six reporters were kidnapped at Escobar's behest. Two more were kidnapped on September 19, though four of the eight were released one-at-a-time in November and December. In September, Colombia's President Cesar Gaviria, who had worked as Luis Carlos Galan's campaign manager and had taken office himself in August, offered leniency and a promise not to extradite any cartel members who turned themselves in to authorities, with the condition that the individual confess to every crime he committed. On November 23, the Medellin cartel proposed a truce to the Colombian government, offering to release several kidnapped hostages in exchange for an official ban on extradition to the U.S. Justice Minister Jaime Giraldo in turn conceded that cartel members who surrendered would only be required to confess to a single crime.

On December 18, Fabio Ochoa turned himself in. By the end of 1990, Colombia's homicide rate had reached 24, 267 killings.

In 1991, Colombia's President Cesar Gaviria, who'd won the election on May 27 of the previous year, announced a policy of non-extradition to the U.S. for drug traffickers who turned themselves in and confessed to their crimes and Colombia's congress amended the country's constitution to bar the extradition of Colombian citizens.

On January 15, Jorge Luis Ochoa surrendered to the Colombian National Police. That same month, David Ricardo Prisco Lopera and his younger brother, Armando Alberto Prisco, were killed by police. On February 16, Juan David Ochoa turned himself in as well.

1991 also marked another appearance by Escobar in Forbe's magazine. The publication listed him as the 62nd richest person in the world and estimated his net worth at $2.5 billion.

In March, Escobar ordered the bombing of Fantasia nightclub in La Dorada, Colombia that left one dead and several people injured. The hit squad members who carried out the attack were paid $17,000.

On April 30, former Justice Minister Enrique Low Murtra was shot to death.

That same month, Escobar sent a messenger to 82-year-old Roman Catholic priest Father Rafael Garcia Herreros with his proposal to meet in the interest of negotiating the release of the two remaining hostages of the 10 that the cartel kidnapped in 1990. On May 12, Garcia was picked up and delivered to a Medellin ranch after being driven for three hours in three separate cars. On May 25, the two remaining hostages were set free. Five days later, Escobar announced through Garcia Herreros that he would surrender to authorities.

A bearded Escobar, wearing jeans and a white leather jacket, surrendered to Colombian police, accompanied by Father Garcia, on June 19, 1991 -- the same day that Colombian legislators, who'd formed the Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution, voted to outlaw extradition. Three members of his hit squads -- John "Popeye"Jairo Velazquez, Otniel "Otto" Gonzalez and Carlos Aguilar -- gave themselves up as well. Escobar was flown by helicopter from the Antioquian jungle, where he'd been hiding, to a specially-built prison of his own design. During transit, he told a reporter, "To these seven years of persecution, I wish to add all the years of imprisonment necessary to contribute to the peace of my family and the peace of Colombia." His 22-hour testimony while in custody included the assertion that his participation in drug smuggling was limited to obtaining a plane and locating an airstrip in 1987 so that Gaviria and five accomplices could transport 400 kilograms of cocaine into France. He also suggested that the Avianca bombing was intended to kill then-presidential candidate Cesar Gaviria Trujillo, who had ultimately changed his flight plans and never boarded the plane.

The Colombian government came to an agreement with Escobar that required him to confess to one crime and serve fifteen years in prison (half of Colombia's maximum sentence), with the caveats that he be allowed to construct the facility, choose his fellow inmates, select the 40 guards who would supervise him and be allowed to conduct business via telephone. Escobar also stipulated that Colombian police weren't permitted within a 3-mile radius of the compound and that the Colombian government provide protection for his family. He was subsequently incarcerated at a newly-built prison, a renovated ranch house, 12 miles south of Medellin and on a hill in the Andes 8,000 feet up, in his hometown of Envigado, nicknamed La Catedral, that boasted a gym, a 50-yard soccer field, Jacuzzis, bars, gourmet food, a barbecue pit, a 60-inch television, a waterbed, billiards and Ping-Pong tables, a cell-phone and a computer for his personal use. Escobar's "cell" was a 380-square foot room with a private bathroom and bars on the door. The facility was ringed by three rows of 5,000-volt electric fencing and sat on 10 acres of land. One-hundred fifty soldiers remained stationed outside the facility.

The day after Escobar's surrender, cartel member Valentin de Jesus Taborda was brought to the prison. That same day, Escobar wrote to a reporter that he'd convinced at least 12 other cartel members to turn themselves in as well.

Two days after Pablo surrendered, his older brother Roberto and cartel bodyguard Gustavo Gonzalez joined him at the prison, having turned themselves in. The two arrived in a seven-vehicle caravan, flanked by armed bodyguards donning bulletproof vests and government representatives. That same day, the Colombian government announced that flights over Medellin would be restricted in the interest of Escobar's safety in light of threats from rival cartels.

Escobar reportedly had 208 visitors, 20 of whom were fugitives, including one with 13 outstanding warrants, during the first month of his prison stay. Meanwhile, his surrender left an estimated 1,500 of his trained sicarios jobless, many of whom applied their skill-sets to kidnapping and robbery to create income.

After hearing reports that Escobar had burned two business associates, William and Gerardo Moncada, to death inside the prison, the Colombian government decided to transfer him to a military facility in Bogota. In addition to the Moncadas, Escobar was also alleged to have ordered the deaths of Mauricio and Fernando Galeano along with 18 of their associates. All 22 were reputed members of the Itaqui cartel, which gave Escobar a percentage of their profits. On July 21, 1992, Escobar took the warden of La Catedral, Jose Rodriguez, and two high-ranking government officials, Deputy Justice Minister Eduardo Mendoza, and Lieutenant Colonel Hernando Navas, hostage after they informed him of their intention to move him. Escobar and associate John Jairo Velazquez held the three at gunpoint. Reportedly, the prison guards voluntarily provided Escobar and his associates with their firearms. During the standoff, Escobar sent a fax to local radio stations requesting President Gaviria's guarantee that neither he nor his 14 fellow inmates would be kidnapped and transported to the U.S. At 4 am the following morning, soldiers stormed the prison, located in Envigado, freed the hostages and detained the majority of the inmates. Escobar, his brother Roberto, Jose Avendano and seven other inmates escaped through a subterranean tunnel and drove away in an army truck. Members of the group were dressed as guards, locals, and one as a woman when they slipped through the 1,600 soldiers surrounding the compound. Escobar reportedly secured his escape by promising $1.4 million in bribes to Sergeant Filiberto Joya and four other members of the army's 4th Brigade. Six individuals, including two guards, were killed during the raid. Ultimately, 28 of the prison’s guards were charged with aiding and abetting Escobar’s escape. Jose Rodriguez and Hernando Navas were fired in the days following the escape as well.

On July 23, Escobar issued a tape recorded message in which he offered to turn himself in, providing the U.N. supervised his surrender. The following day, Escobar's lawyers relayed to Gaviria that their client would turn himself in providing he was returned to La Catedral; the fired guards resumed their jobs; Escobar's family be allowed to visit; and that the CNP have no involvement in his surrender nor his detention. However, Gaviria declined the offer.

Following Escobar's escape, Colombia established the Search Bloc, which consisted of 2,000 U.S.-trained Special Forces members of the police, singularly dedicated to capturing the fugitive. The DEA, CIA and Navy SEALs reportedly joined the manhunt as well.

During his time as a fugitive, an $8.7 million reward was offered for Escobar's capture by the Colombian and U.S. governments. His time on the run and the government crackdown took a toll on cartel business. While the Medellin cartel was responsible for an estimated 70% of cocaine exports from Colombia in 1989, that number dropped to an estimated 40% in 1991.

According Juan Pablo, his father once started a fire with $2 million in cash when Manuela developed hypothermia while the family was hiding in a safe house in the Colombian mountains.

Following an 11-month investigation by the DEA, U.S. Attorney Andrew J. Maloney filed a 14-count indictment against Escobar and his enforcer, Dandeny Munoz-Mosquera, on August 13, charging the two with conspiring to plant the bomb on Avianca flight 203, murder, racketeering, conspiring to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. and engaging in continuing criminal enterprises. The drug charges carried minimum sentences of 10 years to life, while convictions for the Avianca bombing made the death penalty a possibility for the two.

On September 10, Escobar re-ignited what Colombian officials described as a war with authorities that resulted in the deaths of 19 police investigators. Colombia's chief prosecutor, Gustavo de Greiff, responded by freezing a number of accounts tied to the cartel held in Bogota banks in early October. Jose Avendano re-surrendered on September 15. Three days later, Miriam Rocio Velez, the judge who presided over Escobar's murder case for the death of Guillermo Cano, was shot to death by four unidentified assailants.

On October 8, Roberto Escobar, Otoniel Gonzalez and Jhon Jairo Velasquez turned themselves in to police in Itagui, a suburb of Medellin. By this time, the U.S. and Colombian governments had offered a $3.9 million reward for information leading to Escobar's arrest. Additionally, Rafael Galeano, of the Itagui cartel and brother to Mauricio and Fernando, offered a $1.5 million reward for the fugitive.

1993 would mark the seventh year in a row that Forbes magazine placed him on its list of the world's wealthiest people.

On February 16, 10 members of vigilante group Los Pepes torched Escobar's classic car collection. After forcing their way into a south Medellin warehouse where the cartel leader stored his vehicles, they poured gasoline on a Mercedes-Benz, a Porsche, six Rolls-Royces and 20 motorcycles -- all of which was set on fire. The group also dynamited his mother's ranch. Los Pepes was widely believed to be comprised of former members of the Medellin cartel -- including members of the Moncado and Galeano families, Colombian police and members of the Cali drug cartel. Los Pepes murdered 37 people with ties to the Medellin cartel in February alone.

On February 19, 1993, Escobar's wife Maria Victoria, 17-year-old son Juan Pablo and 8-year-old daughter Manuela were stopped at the Medellin airport and blocked from catching a flight to Miami because Escobar had failed to sign papers granting his minor children permission to exit the country. The U.S. Embassy in Colombia revoked Juan Pablo and Manuela's U.S. tourist visas the following day.

On March 3, Escobar, through his attorney, Roberto Uribe Escobar, via faxes of a handwritten statement containing his thumbprint, offered to surrender again providing the U.S. Embassy in Bogota would guarantee his family's safety. The offer, however, was declined. By that time, police and military forces had conducted almost 10,000 raids on labs, homes and businesses tied tothe Medellin cartel and had killed 80 of the organization's members. Escobar also sent a letter to Morris Busby, the U.S.' ambassador in Bogota, denying involvement in the February 26 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City. On March 5, a car bomb injured 27 people and destroyed six buildings in downtown Bogota.

On April 15, a car bomb detonation in Bogota, Colombia's capital, resulted in the deaths of 11 people and injured 200 others. The following day, Los Pepes (the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar), attributing the bombing to Escobar, killed one of his attorneys, Guido Parro, and Parro's 16-year-old son. Fifteen men abducted the two from their Medellin apartment and left their corpses in the trunk of a taxi with a sign that translates to, "What do you think of the trade for the bombing in Bogota, Pablo?"

In May, Escobar made his fifth offer to surrender again via a 2 1/2-page handwritten letter that was slipped under the door of the Medellin offices of the RCN radio network. The letter, signed by Escobar and addressed to Colombia's Prosecutor General Gustavo de Greiff, read, in part: "I'm willing to present myself if I'm given certain written and public guarantees."

In July, former Escobar attorney Salomon Lozano was shot to death by two assailants, believed to be tied to Los Pepes, leaving his Medellin office with his brother, who was injured but survived. Lozano, who'd stopped representing Escobar because of death threats, was shot 25 times.

That November, Gustavo de Greiff informed Escobar's family that he'd recall the bodyguards provided for their protection. On the 28th, Maria Victoria flew to Frankfurt, Germany with Juan Pablo, Manuela, and Juan Pablo's girlfriend seeking refuge but were not allowed to enter the country. They returned to Colombia the following day on a Lufthansa jetliner, after first stopping in Caracas, Venezuela, where they were met at the airport by Colombian police and placed under guard in Bogota's upscale hotel, Tequendama.

On December 2, 1993, the day after his 44th birthday, Escobar and his bodyguard Alvaro "Lemon" de Jesus Agudelo were shot to death, in the Medellin neighborhood Olivos, by the Colombian National Police, who'd located the safe house where he'd been living. Government forces had traced a telephone call that Escobar had made to his son, Juan Pablo. Both men were killed on the rooftop of the two-story house during a raid. Approximately 500 members of the Search Bloc surrounded the residence after tracing a phone call Escobar made to a local radio station on November 28 to complain about Germany's refusal to grant asylum to his family. Escobar and Agudelo, apparently caught off-guard as Escobar was shoeless, exchanged gunfire with the authorities for 20 minutes before they were killed. Escobar, who was armed with two 9-millimeter handguns, sustained three gunshots from rooftop snipers - to the leg, torso and in the ear.

Over 1,000 people showed to view the spot where Escobar was killed. An hour after the shootout, Escobar's mother screamed at police officers stationed at the Medellin city morgue, calling them murderers, when she arrived to identify his body.

Following the announcement of Escobar's death, his teen-aged son Juan Pablo declared on a television news broadcast that, "I'm going to murder one-by-one those sons of bitches who killed my dad." However, he subsequently apologized for his comments on a separate newscast.

U.S. President Bill Clinton sent Colombian President Cesar Gaviria a telegram that read, "Hundreds of Colombians -- brave police officers and innocent people -- lost their lives as a result of Escobar's terrorism. Your work honors the memory of all of these victims."

A mariachi band played the popular Colombian song, "But I keep on Being King" at Escobar's wake, held that night. His funeral, held in Medellin the following day, was attended by thousands, many of whom shouted, "Viva Pablo!". His body was displayed in an open silver casket before members of the crowd carried the coffin in the rain to the burial site at the Montesacro Cemetery.

On October 28, 2006, two days after the death of Escobar's mother, his nephew, Nicholas Escobar, had his uncle's body exhumed in order to collect a DNA sample needed for a paternity test and to confirm that the corpse was actually Pablo.

During his life, Escobar was linked to over 4,000 killings, including 457 policement, 30 judges and three presidential candidates. During his prime, he was estimated to have employed 70,000 workers and to have routinely transported in excess of 11 tons of cocaine per flight to the U.S. via jetliners.

In 1991, Colombia's President Cesar Gaviria, who'd won the election on May 27 of the previous year, announced a policy of non-extradition to the U.S. for drug traffickers who turned themselves in and confessed to their crimes and Colombia's congress amended the country's constitution to bar the extradition of Colombian citizens.

On January 15, Jorge Luis Ochoa surrendered to the Colombian National Police. That same month, David Ricardo Prisco Lopera and his younger brother, Armando Alberto Prisco, were killed by police. On February 16, Juan David Ochoa turned himself in as well.

1991 also marked another appearance by Escobar in Forbe's magazine. The publication listed him as the 62nd richest person in the world and estimated his net worth at $2.5 billion.

In March, Escobar ordered the bombing of Fantasia nightclub in La Dorada, Colombia that left one dead and several people injured. The hit squad members who carried out the attack were paid $17,000.

On April 30, former Justice Minister Enrique Low Murtra was shot to death.

That same month, Escobar sent a messenger to 82-year-old Roman Catholic priest Father Rafael Garcia Herreros with his proposal to meet in the interest of negotiating the release of the two remaining hostages of the 10 that the cartel kidnapped in 1990. On May 12, Garcia was picked up and delivered to a Medellin ranch after being driven for three hours in three separate cars. On May 25, the two remaining hostages were set free. Five days later, Escobar announced through Garcia Herreros that he would surrender to authorities.

A bearded Escobar, wearing jeans and a white leather jacket, surrendered to Colombian police, accompanied by Father Garcia, on June 19, 1991 -- the same day that Colombian legislators, who'd formed the Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution, voted to outlaw extradition. Three members of his hit squads -- John "Popeye"Jairo Velazquez, Otniel "Otto" Gonzalez and Carlos Aguilar -- gave themselves up as well. Escobar was flown by helicopter from the Antioquian jungle, where he'd been hiding, to a specially-built prison of his own design. During transit, he told a reporter, "To these seven years of persecution, I wish to add all the years of imprisonment necessary to contribute to the peace of my family and the peace of Colombia." His 22-hour testimony while in custody included the assertion that his participation in drug smuggling was limited to obtaining a plane and locating an airstrip in 1987 so that Gaviria and five accomplices could transport 400 kilograms of cocaine into France. He also suggested that the Avianca bombing was intended to kill then-presidential candidate Cesar Gaviria Trujillo, who had ultimately changed his flight plans and never boarded the plane.

The Colombian government came to an agreement with Escobar that required him to confess to one crime and serve fifteen years in prison (half of Colombia's maximum sentence), with the caveats that he be allowed to construct the facility, choose his fellow inmates, select the 40 guards who would supervise him and be allowed to conduct business via telephone. Escobar also stipulated that Colombian police weren't permitted within a 3-mile radius of the compound and that the Colombian government provide protection for his family. He was subsequently incarcerated at a newly-built prison, a renovated ranch house, 12 miles south of Medellin and on a hill in the Andes 8,000 feet up, in his hometown of Envigado, nicknamed La Catedral, that boasted a gym, a 50-yard soccer field, Jacuzzis, bars, gourmet food, a barbecue pit, a 60-inch television, a waterbed, billiards and Ping-Pong tables, a cell-phone and a computer for his personal use. Escobar's "cell" was a 380-square foot room with a private bathroom and bars on the door. The facility was ringed by three rows of 5,000-volt electric fencing and sat on 10 acres of land. One-hundred fifty soldiers remained stationed outside the facility.

The day after Escobar's surrender, cartel member Valentin de Jesus Taborda was brought to the prison. That same day, Escobar wrote to a reporter that he'd convinced at least 12 other cartel members to turn themselves in as well.

Two days after Pablo surrendered, his older brother Roberto and cartel bodyguard Gustavo Gonzalez joined him at the prison, having turned themselves in. The two arrived in a seven-vehicle caravan, flanked by armed bodyguards donning bulletproof vests and government representatives. That same day, the Colombian government announced that flights over Medellin would be restricted in the interest of Escobar's safety in light of threats from rival cartels.

Escobar reportedly had 208 visitors, 20 of whom were fugitives, including one with 13 outstanding warrants, during the first month of his prison stay. Meanwhile, his surrender left an estimated 1,500 of his trained sicarios jobless, many of whom applied their skill-sets to kidnapping and robbery to create income.

After hearing reports that Escobar had burned two business associates, William and Gerardo Moncada, to death inside the prison, the Colombian government decided to transfer him to a military facility in Bogota. In addition to the Moncadas, Escobar was also alleged to have ordered the deaths of Mauricio and Fernando Galeano along with 18 of their associates. All 22 were reputed members of the Itaqui cartel, which gave Escobar a percentage of their profits. On July 21, 1992, Escobar took the warden of La Catedral, Jose Rodriguez, and two high-ranking government officials, Deputy Justice Minister Eduardo Mendoza, and Lieutenant Colonel Hernando Navas, hostage after they informed him of their intention to move him. Escobar and associate John Jairo Velazquez held the three at gunpoint. Reportedly, the prison guards voluntarily provided Escobar and his associates with their firearms. During the standoff, Escobar sent a fax to local radio stations requesting President Gaviria's guarantee that neither he nor his 14 fellow inmates would be kidnapped and transported to the U.S. At 4 am the following morning, soldiers stormed the prison, located in Envigado, freed the hostages and detained the majority of the inmates. Escobar, his brother Roberto, Jose Avendano and seven other inmates escaped through a subterranean tunnel and drove away in an army truck. Members of the group were dressed as guards, locals, and one as a woman when they slipped through the 1,600 soldiers surrounding the compound. Escobar reportedly secured his escape by promising $1.4 million in bribes to Sergeant Filiberto Joya and four other members of the army's 4th Brigade. Six individuals, including two guards, were killed during the raid. Ultimately, 28 of the prison’s guards were charged with aiding and abetting Escobar’s escape. Jose Rodriguez and Hernando Navas were fired in the days following the escape as well.

On July 23, Escobar issued a tape recorded message in which he offered to turn himself in, providing the U.N. supervised his surrender. The following day, Escobar's lawyers relayed to Gaviria that their client would turn himself in providing he was returned to La Catedral; the fired guards resumed their jobs; Escobar's family be allowed to visit; and that the CNP have no involvement in his surrender nor his detention. However, Gaviria declined the offer.

Following Escobar's escape, Colombia established the Search Bloc, which consisted of 2,000 U.S.-trained Special Forces members of the police, singularly dedicated to capturing the fugitive. The DEA, CIA and Navy SEALs reportedly joined the manhunt as well.

During his time as a fugitive, an $8.7 million reward was offered for Escobar's capture by the Colombian and U.S. governments. His time on the run and the government crackdown took a toll on cartel business. While the Medellin cartel was responsible for an estimated 70% of cocaine exports from Colombia in 1989, that number dropped to an estimated 40% in 1991.

According Juan Pablo, his father once started a fire with $2 million in cash when Manuela developed hypothermia while the family was hiding in a safe house in the Colombian mountains.

Following an 11-month investigation by the DEA, U.S. Attorney Andrew J. Maloney filed a 14-count indictment against Escobar and his enforcer, Dandeny Munoz-Mosquera, on August 13, charging the two with conspiring to plant the bomb on Avianca flight 203, murder, racketeering, conspiring to smuggle cocaine into the U.S. and engaging in continuing criminal enterprises. The drug charges carried minimum sentences of 10 years to life, while convictions for the Avianca bombing made the death penalty a possibility for the two.

On September 10, Escobar re-ignited what Colombian officials described as a war with authorities that resulted in the deaths of 19 police investigators. Colombia's chief prosecutor, Gustavo de Greiff, responded by freezing a number of accounts tied to the cartel held in Bogota banks in early October. Jose Avendano re-surrendered on September 15. Three days later, Miriam Rocio Velez, the judge who presided over Escobar's murder case for the death of Guillermo Cano, was shot to death by four unidentified assailants.

On October 8, Roberto Escobar, Otoniel Gonzalez and Jhon Jairo Velasquez turned themselves in to police in Itagui, a suburb of Medellin. By this time, the U.S. and Colombian governments had offered a $3.9 million reward for information leading to Escobar's arrest. Additionally, Rafael Galeano, of the Itagui cartel and brother to Mauricio and Fernando, offered a $1.5 million reward for the fugitive.

1993 would mark the seventh year in a row that Forbes magazine placed him on its list of the world's wealthiest people.

On February 16, 10 members of vigilante group Los Pepes torched Escobar's classic car collection. After forcing their way into a south Medellin warehouse where the cartel leader stored his vehicles, they poured gasoline on a Mercedes-Benz, a Porsche, six Rolls-Royces and 20 motorcycles -- all of which was set on fire. The group also dynamited his mother's ranch. Los Pepes was widely believed to be comprised of former members of the Medellin cartel -- including members of the Moncado and Galeano families, Colombian police and members of the Cali drug cartel. Los Pepes murdered 37 people with ties to the Medellin cartel in February alone.

On February 19, 1993, Escobar's wife Maria Victoria, 17-year-old son Juan Pablo and 8-year-old daughter Manuela were stopped at the Medellin airport and blocked from catching a flight to Miami because Escobar had failed to sign papers granting his minor children permission to exit the country. The U.S. Embassy in Colombia revoked Juan Pablo and Manuela's U.S. tourist visas the following day.

On March 3, Escobar, through his attorney, Roberto Uribe Escobar, via faxes of a handwritten statement containing his thumbprint, offered to surrender again providing the U.S. Embassy in Bogota would guarantee his family's safety. The offer, however, was declined. By that time, police and military forces had conducted almost 10,000 raids on labs, homes and businesses tied tothe Medellin cartel and had killed 80 of the organization's members. Escobar also sent a letter to Morris Busby, the U.S.' ambassador in Bogota, denying involvement in the February 26 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City. On March 5, a car bomb injured 27 people and destroyed six buildings in downtown Bogota.

On April 15, a car bomb detonation in Bogota, Colombia's capital, resulted in the deaths of 11 people and injured 200 others. The following day, Los Pepes (the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar), attributing the bombing to Escobar, killed one of his attorneys, Guido Parro, and Parro's 16-year-old son. Fifteen men abducted the two from their Medellin apartment and left their corpses in the trunk of a taxi with a sign that translates to, "What do you think of the trade for the bombing in Bogota, Pablo?"

In May, Escobar made his fifth offer to surrender again via a 2 1/2-page handwritten letter that was slipped under the door of the Medellin offices of the RCN radio network. The letter, signed by Escobar and addressed to Colombia's Prosecutor General Gustavo de Greiff, read, in part: "I'm willing to present myself if I'm given certain written and public guarantees."

In July, former Escobar attorney Salomon Lozano was shot to death by two assailants, believed to be tied to Los Pepes, leaving his Medellin office with his brother, who was injured but survived. Lozano, who'd stopped representing Escobar because of death threats, was shot 25 times.

That November, Gustavo de Greiff informed Escobar's family that he'd recall the bodyguards provided for their protection. On the 28th, Maria Victoria flew to Frankfurt, Germany with Juan Pablo, Manuela, and Juan Pablo's girlfriend seeking refuge but were not allowed to enter the country. They returned to Colombia the following day on a Lufthansa jetliner, after first stopping in Caracas, Venezuela, where they were met at the airport by Colombian police and placed under guard in Bogota's upscale hotel, Tequendama.

On December 2, 1993, the day after his 44th birthday, Escobar and his bodyguard Alvaro "Lemon" de Jesus Agudelo were shot to death, in the Medellin neighborhood Olivos, by the Colombian National Police, who'd located the safe house where he'd been living. Government forces had traced a telephone call that Escobar had made to his son, Juan Pablo. Both men were killed on the rooftop of the two-story house during a raid. Approximately 500 members of the Search Bloc surrounded the residence after tracing a phone call Escobar made to a local radio station on November 28 to complain about Germany's refusal to grant asylum to his family. Escobar and Agudelo, apparently caught off-guard as Escobar was shoeless, exchanged gunfire with the authorities for 20 minutes before they were killed. Escobar, who was armed with two 9-millimeter handguns, sustained three gunshots from rooftop snipers - to the leg, torso and in the ear.

Over 1,000 people showed to view the spot where Escobar was killed. An hour after the shootout, Escobar's mother screamed at police officers stationed at the Medellin city morgue, calling them murderers, when she arrived to identify his body.

Following the announcement of Escobar's death, his teen-aged son Juan Pablo declared on a television news broadcast that, "I'm going to murder one-by-one those sons of bitches who killed my dad." However, he subsequently apologized for his comments on a separate newscast.

U.S. President Bill Clinton sent Colombian President Cesar Gaviria a telegram that read, "Hundreds of Colombians -- brave police officers and innocent people -- lost their lives as a result of Escobar's terrorism. Your work honors the memory of all of these victims."

A mariachi band played the popular Colombian song, "But I keep on Being King" at Escobar's wake, held that night. His funeral, held in Medellin the following day, was attended by thousands, many of whom shouted, "Viva Pablo!". His body was displayed in an open silver casket before members of the crowd carried the coffin in the rain to the burial site at the Montesacro Cemetery.

On October 28, 2006, two days after the death of Escobar's mother, his nephew, Nicholas Escobar, had his uncle's body exhumed in order to collect a DNA sample needed for a paternity test and to confirm that the corpse was actually Pablo.

During his life, Escobar was linked to over 4,000 killings, including 457 policement, 30 judges and three presidential candidates. During his prime, he was estimated to have employed 70,000 workers and to have routinely transported in excess of 11 tons of cocaine per flight to the U.S. via jetliners.