by Ran

Jose Santacruz-Londono was born on October 1, 1943 in Cali, Colombia. As a teen he attended high school with Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez-Orejuela. He eventually completed four years of engineering studies at Bogota's De Valle University of the Andes.

In 1969, Santacruz co-founded the Los Chemas gang with Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela. That same year, the seven-member gang was suspected of the kidnapping of two Swiss citizens -- a student, Werner Jose Straessel and diplomat Herman Buff -- for $700,000 ransom. By 1969, he'd bought paid three taxicabs, which he'd paid for in cash.

Initially engaging in counterfeiting kidnapping-for-ransom and marijuana trafficking, Los Chemas eventually became involved in drug trafficking, smuggling Bolivian and Peruvian coca paste into Colombia for processing into cocaine.

The group later recruited other organizations under one umbrella, which became known as the Cali drug cartel --- named for the Colombian city in which it was based. The cartel, an alliance of five separate and distinct drug trafficking organizations, was comprised of: the Rodriguez-Orejuela brothers organization; the Jose Santacruz-Londono organization; the Helmer "Pacho" Herrera Buitrago organization; the Urdinola-Grajales brothers organization; and the Grajales-Lemos and Grajales-Posso organization. Eventually, Miguel took over as head of the daily operations of the organization while Santacruz-Londono managed the international transportation networks.

In the early 1970s, Helmer "Pacho" Herrera was dispatched to New York City to establish a distribution network. He created nearly-independent cells, each overseen by a "celeno" (cell manager). Each celeno reported to cartel-associate Jorge Alberto Rodriguez, who answered to the cartel leaders.

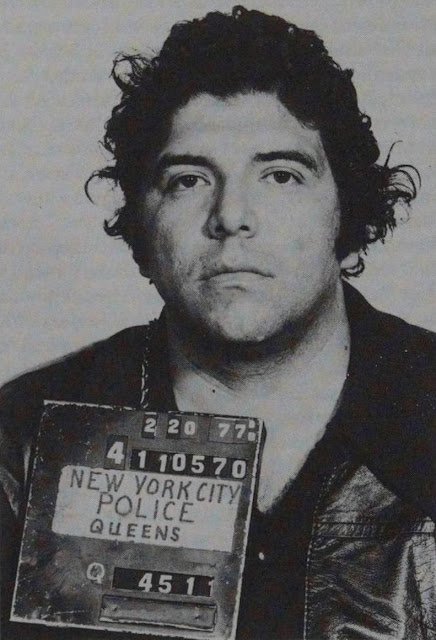

Santacruz was arrested in 1976 and again -- this time on a weapons violation -- on February 20 of the following year in Queens, New York.

Gilberto Rodriguez initially sent his childhood friend Giraldo Soto to New York City in 1975 in order to help with the distribution networks but Santacruz took over New York operations when Soto was arrested in 1978.

By 1980, Santacruz and his wife, Amparo Castro de Santacruz, were living in a lavish home in the upscale Ciudad Jardin neighborhood with 15 marble-covered bathrooms. He gave his interior decorators buy-money and payments in a Gucci bag full of cash -- upwards of $1 million at a time.

Santacruz also owned a cattle ranch, restaurants and hundreds of pieces of Cali real estate.

After being denied the use of Cali's prestigious Club Colombia for his daughter's quinceanera, Santacruz reportedly had a mansion constructed to resemble the facility that houses the exclusive club. He also ordered the construction of a 30,000 square foot mansion called Casa Blanco, designed to look like the White House. He also sent his daughter Ana Milena Santacruz to the U.S. to attend Boston's Pine Manor Girl's School.

Santacruz established a collection of stash houses, used for storing cocaine and cash, throughout Brooklyn and Queens. He oversaw cocaine production, processing, and distribution. Besides New York, he also established distribution centers in Miami, Houston and Los Angeles.

1980 also marked Santacruz's indictment for operating a continuing criminal enterprise in Brooklyn, NY. The charges were brought following investigators uncovering a cartel safe house used for storing cocaine and machine guns equipped with silencers.

By 1981, the Cali cartel and their biggest competitors the Medellin cartel had agreed to divvy up distribution points in the U.S. Where the former chose New York City, the latter agreed to utilize Miami, leaving Los Angeles free for either organization.

Cali's transport methods contrasted sharply with the rival Medellin cartel's preference for light planes and speedboats, instead opting for hidden shipments aboard ocean-freighters. The Cali cartel also enlisted Mexican criminal organizations to transport the cocaine from Central America into the U.S.

The Cali cartel also differed from their Medellin competitors in that they employed the use of cells, which served to prevent potential informants from identifying many cartel members because they were only aware of the few with whom they interacted.

Cali, Colombia

In 1981, Santacruz was stopped by narcotics agents in a JFK Airport parking lot. However, since they were tracking the alias he used for his U.S. dealings, Victor Crespo, they allowed him to leave upon seeing the name Jose Santacruz Londono on his passport.

By 1984, Santacruz had begun to establish a distribution network in Houston, TX, using private planes. Both he and Gilberto Rodriguez were indicted in Brooklyn that year for importing cocaine into the U.S. for distribution in New York between 1978 and 1984. By that time, had an apartment in Bogota that boasted $75,000 worth of remodeling. That same year, he financed the renovation of the home of his mistress, Marley, and the three children they shared.

Gilberto Rodriguez, who'd been caught with a Venezuelan passport in Spain, was put on trial with Santacruz in Cali. However, the presiding judge refused to admit evidence submitted by the DEA in connection with U.S. indictments in LA and New York City and the two were acquitted in 1986.

Santacruz routinely wore disguises, so as to conceal his identity from law enforcement, and surrounded himself with armed bodyguards. The cartel used thousands of telephone calls and faxes each month to conduct business.

The organization routinely concealed cocaine in shipments of items as diverse as hollow lumber, chlorine cylinders, lye and frozen foods such as broccoli and okra.

In April of 1988, Customs officials seized 3,270 kilograms of the cartel's cocaine hidden in lumber planks, in Tarpon Springs, FL. That same year, Customs agents discovered 2,270 kilograms of cocaine concealed in blocks of chocolate exported from Ecuador. Back in Colombia, Santacruz ordered the bombing of Pablo Escobar's home, which resulted in his daughter losing her hearing.

That same year, one of Santacruz's workers, Luis Ramos, was arrested at a Queens stash house by the DEA, who seized $7.8 million. Within weeks, another of Santacruz's employees was arrested in possession of $2.2 million in cash and 2,000 kilograms of cocaine. In 1989, Customs agents police in New York uncovered 5,000 kilograms of coke belonging to Santacruz-associate Luis "Leto" Delio Lopez in 252 drums of powdered lye. That same year, the FBI and New York police unearthed hundreds of vehicles tied to the cartel with false registrations obtained from Department of Motor Vehicles workers. DMV employees were paid $100 for each registration for vehicles equipped with hidden compartments used to ship cocaine and cash.

While the Cali cartel's main rival, the Medellin cartel, routinely engaged in narco-terrorism, the Cali bosses preferred bribing government officials to killing them. The two organizations also dominated different markets in the U.S. While the Medellin cartel controlled Miami, Cali held sway over New York and Washington, D.C. as distribution hubs. However, in June of 1989, the two cartels began to war with one another to determine which would rule New York as a cocaine distribution point.

Santacruz was suspected of orchestrating the 1989 murder of Antonio Roldan Betancur, the former Governor of Antoquia.

That same year, his mistress, Marley, died under mysterious circumstances and Santacruz and his wife moved Marley's four children in with them. Around the same time, he had his ranch house outfitted with a five-sink kitchen, leather carpets, palm trees and a fountain. He also rented an apartment on Manhattan's West 57th Street for $8,365 per month.

In 1990, the DEA unsuccessfully attempted to apprehend Santacruz in Italy during the World Football Cup. They did, however, manage to have over $60 million of his fortune in bank accounts frozen -- $12 million in New York City alone and a warrant was issued for his arrest in Brooklyn.

On May 2, a bomb in a car parked outside of a Cali supermarket reportedly owned by Gilberto Rodriguez, detonated and killed four people. Four days later, 220 pounds of explosives inside a fruit truck went off near Cali. This time no one was killed.

In September of 1990, Medellin sicarios (assassins) killed 19 Cali cartel workers at a Cali ranch.

On October 14, 1990, Colombian physician Rafael Lambrano was shot to death on the orders of Guillermo L. Restrepo Gaviria, Santacruz's chief lieutenant and a New York cell manager for the cartel. Lambrano, who had become an informant for the DEA, was approached by cartel worker John Harold Mena and two associates in the parking lot of a Miami restaurant at which he'd been dining. Mena, who was paid $20,000 for the job, and the others had deflated Lambrano's tires and one of them shot him with a silenced automatic handgun when he came out to the car. Restrepo was also the brother of Mena's girlfriend.

In November of 1990, Santacruz allegedly ordered the shooting death, through Restrepo, of shipping executive John R. Shotto in Baltimore in response to Shotto's testimony in a 1989 civil suit regarding the Cali cartel's clandestine $3.6 million investment in a 248-foot cargo freighter, the M.V. Liberty,

with which they'd planned to use to smuggle drugs into the city. On September 14, 1991, John Harold Mena drove triggerman Juan Carlos Velasco, who shot Shotto and fellow executive Raymond B. Nicholson Jr., with whom he'd had a business meeting, from the car.

That same year, Santacruz was placed on the U.S.' list of the 12 most wanted Colombian drug traffickers. Meanwhile, Mena was promoted to business manager, a job that came with a $60,000 annual salary. Mena later testified that he supervised the distribution of 3,000 kilograms of cocaine during his first year in his new position.

In 1991, the DEA's Miami branch seized a 15-ton shipment of cocaine hidden in concrete fence posts after a drug-sniffing dog detected the narcotics at the Port of Miami. On June 18, police seized 4,444 pounds of cocaine from a lab in Cali. By this time, the cartel had labs, with more than 20 employees each, producing over 250 kilograms of cocaine each week.

Meanwhile, Colombia implemented measures to better ensure the safety of judges for fear of reprisals and pre-emptive attacks by cartel triggermen. The courts began employing two-way mirrors, screens and devices to distort the voices of judges during trial proceedings in order to conceal their identities.

The same year, Santacruz's Parkinson's-addled father-in-law Heriberto Castro Meza deposited $36 million in various bank accounts throughout Europe for him during a trip on which he was accompanied by his daughter, Amparo.

By mid-1991, the Cali cartel had grown to 5,000 employees and on July 12, Colombia's President Cesar Gaviria stated during an interview conducted in Bogota, "We have the same policy toward the Cali cartel as toward the Medellin cartel." "Simply because the Medellin cartel bore the greatest responsibility for narco-terrorism, we concentrated the largest amount of our efforts there. But our policy is the same." But while the Colombian government's war against the Medellin cartel dealt a tremendous blow to its business, the Cali cartel saw its own share of Colombia's cocaine exports to the U.S. rise from 30 to 60% from mid-1989 to mid-1991. During this time the Cali cartel made significant inroads into the European market -- specifically, England, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands -- via ports in Spain and the Netherlands. The group also encroached on the Medellin cartel-controlled distribution centers of Los Angeles and Miami.

Also in 1991, Santacruz allegedly ordered the murder of New York-based, Cuban American journalist Manuel de Dios Unanue in Queens, NY. De Dio was fatally shot at the Meson Asturias restaurant in Jackson Heights on March 11, 1992. Seventeen-year-old Colombian Wilson Alejandro Mejia Velez, who was paid $4,500 the following day, shot De Dios twice in the back of the head with a 9mm Baretta handgun. The former editor-in-chief of the El Diario-La Prensa newspaper had regularly reported on Santacruz's activities for the cartel. Mena testified on behalf of the government at Mejia's February 1993 trial. While Mena's mother was placed in protective custody and moved out of Colombia, his father, uncle and aunt were all subsequently murdered. Mejia was given a life sentence for De Dios' killing in March of 1993.

While the Cali cartel generally eschewed the narco-terrorism employed by their Medellin rivals, the Cali leaders did initiate a campaign of murder aimed at ridding their hometown of those they labeled "desechables" (Spanish for "disposables") -- the homeless, prostitutes and homosexuals. The cartel's "grupos de limpieza social" ("social-cleansing groups") left signs on the corpses of some of their victims reading: "Cali limpia, Cali linda" ("Clean Cali, beautiful Cali"). But most of the corpses were thrown into the central Cauca River, which consequently came to be known as "The River of Death" by locals.

In late 1992, at the conclusion of the DEA's three-year investigation, Operation Green Ice, the Cali cartel's global network was so thoroughly infiltrated that investigators arrested 165 members of a drug trafficking and money-laundering conspiracy and seized $47 million from associated bank accounts. In an uncharacteristic show of violence, cartel leaders ordered suspected informants immersed in barrels filled with acid. In order to shield itself from money-laundering prosecutions, the cartel resorted to transporting the vast amounts of cash generated from cocaine sales back to Colombia via container ships and cargo planes. Some of the cash was converted into money orders and travelers checks.

In light of what the U.S. viewed as a passive response to the Cali cartel's activities by the Colombian government, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Jesse Helms urged ending economic aid to Colombia until the country's government took more steps to stifle narcotics trafficking.

In April of 1995, the Colombian government offered a reward of $625,000 for information leading to Santacruz's arrest. On June 7, a federal indictment charging Santacruz with one count of conspiracy to possess and distribute cocaine and another count of conspiracy to conceal the proceeds, was unsealed in Brooklyn, NY. Authorities subsequently froze over $30 million of Santacruz's money he'd deposited in various European bank accounts under the names of close friends and family. Santacruz had accounts in England, France, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Austria, Luxembourg, Monaco and the Netherlands -- all supervised by Harvard-educated money manager Jose Franklin Jurado Rodriguez. Jurado, who'd also been named in the indictment, had himself been arrested in 1990 in Luxembourg and extradited to the U.S. on money laundering charges in 1994.

Michael Abbell, former head of the international affairs office of the Justice Department's criminal division, who took Gilberto Rodriguez on as a client after leaving his government post, was one of three U.S. attorneys indicted as part of a narcotics conspiracy on June 5, 1995. He was accused of intimidating witnesses and fabricating evidence for the Cali cartel. Another defendant, attorney William Moran, was charged with revealing the identity of a confidential informant, who was subsequently murdered, to the cartel. The indictments were a result of a widespread investigation, nicknamed Operation Cornerstone, into the cartel. Ironically, Abbell was charged with extraditing drug traffickers to the U.S. when he worked for the Justice Department. Operation Cornerstone resulted in over 60 indictments, including charges for the Rodriguez brothers, Santacruz and the cartel's fourth-in-command, Helmer "Pacho" Herrera Buitrago. The investigation concluded that since 1983, the cartel had shipped 200,000 kilograms of cocaine to the U.S.

Following raids on cartel residences and places of business in 1995, DEA agents discovered a laptop equipped with advanced software from Israeli intelligence that enabled Santacruz to monitor nearly every telephone call placed in Cali and Bogota as well as to identify any wiretaps placed on his own telephone lines. Santacruz, who supervised the cartel's counter-surveillance operations, also placed a cartel operative inside the area telephone company. The cartel's routine surveillance even included telephone calls made from the Ministry of Defense and the U.S. Embassy.

Santacruz also reportedly underwent several cosmetic surgical procedures in an effort to conceal his true identity.

On July 4, 1995, Santacruz was arrested, while drinking rum and vodka with friends in a Bogota barbecue restaurant, by Colombian authorities. He told the arresting officers, "Take it easy. It's me.", and paid his bill before being escorted out of the restaurant. Santacruz was eventually taken to Bogota's La Picota Prison, from which he escaped on January 11, 1996 after bribing several guards. Subsequently, a $2 million reward was offered for information leading to his capture.

Santacruz was shot to death by police near Medellin on March 5, 1996. While his death was initially reported as the result of a shootout, it was later revealed that he was re-apprehended, tortured and killed while in custody. His body was flown back to Cali two days later.

From the 1980s to the mid-1990s, Santacruz regularly shipped 8,000 kilograms per week to New York. At the time of his shooting, his personal net worth was estimated to be $250 million.

1 comment:

Thank you for the article.

Post a Comment